Update #2: Read by full response to Brennan’s review here. The ideas speak for themselves.

Update: Jason apparently revised his review after sending to me and submitting it to the journal NDPR. You can view the original version here. Not too much gets changed – except now he tries to give even less credit than before, by changing lines like:

Square One refutes what I call super-duper radical skepticism, but not radical skepticism.

And turning it into:

Square One repeats the arguments which refute super-duper radical skepticism, but it does not respond to radical skepticism.

So now, it’s no refutation – it’s repeating somebody else’s argument! You can’t make this stuff up. The updated review is posted below, along with my initial commentary.

After getting some good advice, I’ve decided to post Jason Brennan’s review and forgo the possibility of getting it published in a journal (which, as it appears, is extremely unlikely). The ideas speak for themselves. Brennan does not attempt to hide the fact that he wishes to discredit the book rather than treat it fairly. It’s filled with transparent insults like, “Laypeople would be better off having no exposure to philosophy at all.”

The entire review is based on a strawman of the purpose of my book. Square One is extremely limited in scope and tightly argued. So rather than address the ideas in the book, he spends nearly the entire review writing about what isn’t in the book, by claiming Square One is supposed to be a complete theory of epistemology. It obviously isn’t – as will be crystal clear to anybody that reads the 125-page book.

Square One would indeed be terrible if it claimed to present a full theory of knowledge. And it would also be a terrible book about the foundations of biology. There are all kinds of ideas I don’t write about, because the book isn’t about those ideas. Fortunately, it’s a book that is very limited in scope, and even according to Brennan, I accomplish exactly what I want to accomplish – the laws of logic are indeed foundational, absolute, and you can be certain of them.

Don’t take my word for it. Here is the review he sent me, in its entirety. If you don’t want to read it, you can also listen to me go through most of it in this video:

If you have not read Square One yet, you can pick up a cheap copy online, or you can get a free preview here.

Steve Patterson, Square One: The Foundations of Knowledge. CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2016. 125 pages (ppk), $9.99. ISBN: 978-1540402783

Review by Jason Brennan, Georgetown University

Philosophy could use a Tim Harford (The Undercover Economist) or a Steven Landsburg (The Armchair Economist and More Sex is Safer Sex). Both write lucid, engaging books which teach a popular audience the central insights of economics, even if these books do not produce new knowledge.

Steve Patterson wants to do even more. He wants not only to spread philosophical wisdom to the masses, but also to shake philosophy from its dogmatic slumbers. He’s got an audience. As I write this, Square One: The Foundations of Knowledge is among the top 200 epistemology books on Amazon, outselling (older) introductory books by world-class epistemologists like Keith Lehrer, Alvin Goldman, Ernest Sosa, or John Pollock.

In chapter two (and to some degree in later chapters), Patterson presents a range of arguments for radical skepticism. For instance, some skeptics say that claiming to possess knowledge is arrogant. Other skeptics say that to have any knowledge would require us to have far more information that we can possibly acquire. Others claim that knowledge presupposes faith in God. Others claim that natural selection would not evolve truth-tracking brains. Others says we’re stuck inside our subjective perspectives and cannot access objective facts. Still others say that the imprecision or vagueness of language means we lack knowledge, because our language doesn’t carve out nature by its joints. Still others claim that logic and mathematics are Western inventions and cultural artifacts, or that logic and mathematical truths are simply empty tautologies derived from arbitrary definitions and axioms.

Patterson intends to debunk these skeptical arguments. The back cover of Square One declares, “Truth is discoverable. It’s not popular to say. It’s not popular to think. But you can be certain of it.”

Chapter three—the best chapter in the book—responds to radical skepticism about logic. But his arguments are nothing new. Patterson uses the same argument students learn in week one of PHIL 101: Criticisms of the basic rules of logic are self-refuting. Any argument purporting to invalidate logic presupposes the truth of the rules of logic. Poststructuralist or postmodernist complaints about logic are internally incoherent. Fair enough, but Patterson simply repeats other philosophers’ arguments without attribution.

Throughout Square One, Patterson promises to help the reader discover “certain truth” (e.g., pp. 9, 13, 14, 15, passim). It is unclear whether Patterson understands the difference between A) the certainty of a proposition itself versus B) the certainty of one’s belief in that proposition. He often conflates logical necessity with epistemic certainty (e.g., p. 54). He’s conflates the modality of propositions with one’s epistemic justification in believing them. But these are of course distinct.

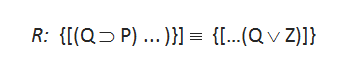

To illustrate, consider true statement R, a properly constructed formula in sentential logic, which I’ve write below in an abbreviated form:

In unabbreviated form, R is very long. R has 14,000 particles and on the left side of the biconditional and 15,000 particles on the right.

Now, R is not only true, but true in all possible worlds. But since R is so darn long, even the world’s best logician would have less than perfect epistemic certainty about the truth of R. She would reasonably worry, even if she uses a computer, that she made a mistake when she tried to calculate the truth value for R. This isn’t because she doubts the validity of logic; rather, she doubts herself.

Similar remarks apply to moderately difficult math problems. When I took my last math test in college, I knew my answers were either necessarily true or false. But I also know that I am fallible, so my degree of credence in my answers was less than 100%. I doubt myself, not the universal validity of mathematics.

Patterson glosses over or ignores this problem. Even if we grant, as we should, that logical truths are necessary truths, that doesn’t mean we have epistemic certainty about all or even most of them. There are an infinite number of necessary truths in logic and math. But some of these are hard to figure out, so we cannot be certain we got them right, though we know all the true statements are necessarily true and the false statements are necessarily false. In short, it’s reasonable to be skeptical about many of logical or mathematical beliefs not because there’s a problem with logic or math but because we know we make mistakes.

This problem aside, Patterson successfully recites the arguments which refute skepticism about the basic axioms of logic. But what about skepticism about other beliefs? For instance, how do I know I’m not a brain in a vat? May I trust my senses? Is it possible that I am being radically deceived by a demon? If so, how can I be justified in thinking I really do have two kids or that I really am 37 years old? The axioms of logic do little to answer these questions, and Patterson does even less.

This means Patterson’s critique of skepticism is rather narrow. To illustrate, consider these two forms of skepticism:

Super-duper Radical Skepticism: We can know nothing, not even the rules of logic or mathematical truths. We don’t even know whether super-duper skepticism is justified!

Radical Skepticism: We have knowledge of some mathematical and logical truths, some analytically true statements, and small number of metaphysical claims. But we are not justified in most of our beliefs about the outside world, such as the belief that the universe is more than two seconds old, or that we have hands, or that we are not in the Matrix, or that Steve Patterson really did write Square One, etc.

Square One repeats the arguments which refute super-duper radical skepticism, but it does not respond to radical skepticism. So, Patterson is right that truth is discoverable, but he doesn’t show us how to discover most of the interesting truths.

Square One is meant to present a theory epistemology, but it is unclear whether Patterson knows what epistemology is. He does not even attempt to answer the basic questions of the field.

Let’s briefly review. The subfield of epistemology studies the nature of knowledge. Its central questions include A, B, and C:

A) What is knowledge?

For instance, epistemologists generally agree that three necessary (but not sufficient) conditions for a person to know that P are 1) the person must believe P, 2) P must be true, and 3) the person must be justified in believing in P.

This brings us to the most important question in epistemology.

B) What distinguishes justified from unjustified belief?

For instance, if you believe that penicillin kills bacteria because the evidence overwhelmingly shows that, then you are justified; if you believe that Santa is real on the basis of wishful thinking, you are not justified. But there are plenty of interesting questions about what takes to be justified. To be justified in believing P, must it be impossible for you to be wrong? How does evidence in scientific reasoning work? When does the testimony of others confer justification, and when doesn’t it? Am I justified prima facie in trusting my senses?

Patterson makes almost no attempt to answer either question A or B. He discusses some examples of justified or unjustified belief, though, again, it’s unclear whether Patterson understands the difference between 1) the truth of a proposition and 2) the epistemic justification an individual person has in believing that proposition.

Epistemology also asks a third, closely related question:

C) Does knowledge have a structure? How do justified beliefs relate to one another?

There are many competing theories trying to answer this question. Patterson seems to think there are only two: coherentism and foundationalism. He does not mention or respond to the any of the theory major theories.

Patterson seems to want to defend a foundationalist theory of knowledge in Square One: The Foundations of Knowledge. He laments:

Modern philosophy is dominated by schools of thought that deny the existence of foundations. They argue that worldviews aren’t like trees; they are more like spider webs. Each part is connected together with no clear hierarchy of importance. Each thread is fallible and can be removed without destroying the whole structure. (2)

But there are two big problems with this claim.

First, that’s an incorrect description of what coherentists actually think. In fact, most coherentists agree that the web of beliefs is structured. Some beliefs carrying more weight than others. Removing some beliefs (e.g., “There is an external world”) would severely damage the web; removing others (e.g., “There is hot sauce in the fridge”) would not. Further, coherentists agree that some beliefs are certain or or capture logically necessary propositions, though they deny this makes such beliefs foundational.

Second, Patterson is right that foundationalism is now unpopular, but, pace Patterson, so is coherentism. The PhilPapers survey finds that only 26.2% of philosophy faculty accept any form of internalism, while 43.7% accept some form of externalism. The numbers are roughly the same for specialists in epistemology.[1]

All this aside, Square One never actually gets around to defending foundationalism or showing us what the foundations of knowledge are. He provides lots of unoriginal metaphors about trees and roots, houses and foundations, and the like. He declares in chapter three that logical axioms are among the foundations (32). But he never tries to show us 1) which beliefs (aside from logical axioms) are basic, 2) how these basic beliefs justify our non-basic beliefs, or 3) which mental states justify the majority of our non-mathematical beliefs. He never shows us 4) that the axioms of logic are the foundations of most of our beliefs (other than of derivative logical truths). He therefore provides no evidence that our beliefs form a foundationalist structure. He responds to none of the common objections to foundationalism; he may be unaware of them.[2]

Patterson asserts many times that the axioms of logic are the foundations of our beliefs. He fails to argue for this claim though.

He’s right, of course, that all of our beliefs should be compatible with logic. But it doesn’t follow that these axioms somehow justify most of my beliefs or that my beliefs are “grounded” in logic in any interesting way. I believe I own more than two guitars, that I have brown hair, that I have thirty-two teeth, that Australia is bigger than Rhode Island, and so on. If any of these beliefs violated the axioms of logic, they would necessarily be false. But other than that, there’s no obvious way in logic provides the roots from which these beliefs grow. My belief that I own more than two guitars is not derived from the law of identity, nor does the law of identity confer justification on that belief.

Instead, the justification of these beliefs depends on various perceptual states I’ve had and on the reliability of the testimony I’ve received from others. If Patterson intends to defend foundationalism, his project is radically incomplete. He’s not even 1% of the way there.

Patterson does not even attempt to refute rival epistemological theories. That’s not some minor oversight. To defend foundationalism, he needs to show the theory does a better job explaining the phenomena than the rival theories. Defending an epistemological theory is like selling car; if you want us to buy the 3-series you need to show us it’s better than the C Class.

To summarize: Patterson does a decent job reciting the arguments against what I call “super-duper radical skepticism.” He does almost nothing to defeat what I call “radical skepticism”. He does not actually bother to defend a foundationalist theory of knowledge. Still, his book beautifully written, takes only an hour to read, and at least defeats super-duper radical skepticism. We might ask: Is this at least a good book for a lay audience?

Unfortunately, the answer is no, for two big reasons. First, there are far better books, such as Thomas Nagel’s The View from Nowhere or Michael Huemer’s Skepticism and the Veil of Perception. Second, Patterson’s book is chock full of elementary errors. Nearly every page contains some major mistake or conflates two or more distinct ideas together. Laypeople would be better off having no exposure to philosophy at all.

For instance, on p. 61, he says that “The study was unbiased” and “The study was conducted properly” are “concepts”. But these are propositions, not concepts. On p. 83, he says, “Mathematical truths, if carefully constructed, can also be immune from the possibility of error.” But this once again conflates metaphysical/logical necessity with epistemic certainty/justification or with a person’s math skills. Mathematical truths cannot be in error, but I could be in error when I try to do a math problem or when I form beliefs about mathematics. On p. 36, he discusses the phrase “The elephant outside my window”. He says that since there isn’t actually an elephant outside his window, then the referent of “elephant” is an idea or a concept in someone’s head. But that’s just sloppy. What he really means is that he has a concept of “the elephant outside my window” in his head, but the concept has no referent in this case. The referent is not the concept itself.

In the end, Square One is a beautifully written text, with lucid prose and delightful metaphors. What’s new isn’t good and what’s good isn’t new. Patterson could condense the entire thing to about 3000 words. Five stars for style; one star for substance.

[1] https://philpapers.org/surveys/results.pl?affil=Philosophy+faculty+or+PhD&areas0=11&areas_max=1&grain=coarse

[2] See, e.g., John Pollock and Joseph Cruz, Contemporary Theories of Knowledge (Boulder: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999), pp. 60-65; Keith Lehrer, Theory of Knowledge (Boulder: Westview Press, 2000), pp. 50-95); Ali Hasan and Richard Fumerton, “Foundationalist Theories of Epistemic Justification,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 edition), ed. Edward N. Zalta, URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/justep-foundational/>