Few things are as intuitively obvious, yet philosophically challenging, as the existence of free will. Do we have it? Our intuition screams “Of course!”. But our rational analysis screams, “Of course not!”.

Every day, we’re bombarded with confirmatory experiences: we choose this food over that food. We choose to follow or break the speed limit. We choose what we say, what we write. Surely, it seems clear, that for all of our choices, we could have chosen otherwise.

This morning, I drank water with breakfast. I could have chosen orange juice. To think I couldn’t have seems ludicrous. Yet, if our intuition is accurate – if we indeed have the ability to choose – we’re forced to accept a set of radical conclusions.

Though, even if our intuitions are wrong, and we do not actually have the ability to choose, we’re still left with a set of unpalatable conclusions. Either way, free will is a profound philosophic problem.

There’s a fashionable critique of free will that says, “The very concept of free will is incoherent; therefore, it obviously doesn’t exist.”

This article will not make the case for or against the existence of free will. Instead, it will defend its conceptual coherence. Free will is not a nonsensical idea, and it might exist.

First Things First

We need to define “free will”. It is simply “the ability to choose between possible alternatives.”

Therefore, exercising free will is “the act of choosing between possible alternatives.”

If I possessed free will at breakfast, then I had the ability to choose between orange juice and water. When I made my decision, I used this ability. Seems straightforward.

Central to the idea of free will (and philosophy in general) is the concept of causality – the presupposition that effects have causes; that the circumstances we see in the world are the result of prior circumstances; that all phenomena have a causal connections to their preceding states. For any event Z, you can meaningfully ask, “What was the cause of Z?”, and meaningfully answer, “X and Y were the cause of Z”.

Causality may or may not exist; that’s an argument for another time. For this article, I will assume that causality exists.

Determinism and Indeterminism

To understand any discussion about free will, we need to understand the distinction between determinism and indeterminism. I like to think of these concepts as statements about inputs and outputs.

Determinism simply states that, “Any given set of inputs will yield a necessary output.” Or, “For any output, it is the result of a certain set of inputs.”

Indeterminism, by contrast, states that, “Any given set of inputs will not necessarily yield a particular output.” Or, “For any output, it is not a necessary result of preceding inputs.”

The argument against free will goes like this: either determinism or indeterminism is true, with no alternatives, and neither option leaves room for free will.

The determinist argument is easy to understand. Take my decision at breakfast. It appeared as if I chose water over orange juice. But what was the cause of my decision? “The act of drinking water” was the output, and it had several inputs – my thirst, the motion of my fingers grasping the cup, the laws of physics, the neurological happenings in my brain and body, etc. Let’s say that, “My decision to drink water” was also an input.

But notice: for each input, we can also treat it as an output. What was the cause of my thirst in the first place? What was the cause of the motion in my fingers? The neurological firing in my brain? Given the presupposition of causality, we know that each input will also be an output of something prior.

So what happens if we treat “my decision to drink water” as an output? Well, it had certain inputs – my beliefs about water’s ability to satisfy my craving, the environmental surroundings I found myself in, my preferences for water over orange juice, my valuing satiation to thirst, etc.

But each of these inputs, too, is also an output. What was the cause of my beliefs about water? What was the cause of my environmental surroundings? My preferences, and my values?

We can keep going on, treating our inputs as outputs, and we’ll never find room for free will. Instead, we’ll find a whole bunch of inputs that we certainly aren’t in control of. Ultimately, who’s responsible my preference of water over orange juice? I didn’t “choose to prefer” one to the other. I just do. I didn’t choose all of my environmental surroundings – I didn’t even choose what country I was born into. Heck, I didn’t even choose to exist!

So, if I’m not in control of the inputs of my decisions, how could I possibly conclude that I control the output of my decisions?

Thus, the determinist rules out the existence of free will simply by analyzing cause and effect.

What about the indeterminist? They claim, “For any output, it is not necessarily caused by a particular set of inputs.” In other words, randomness is an essential feature of the universe. Given a precise set of inputs, you do not have a necessary outcome. Instead, reality might be fundamentally probabilistic – still incorporating some degree of causality, but not without exceptions.

This line of thinking is particularly popular with the quantum-physics-mysticism crowd.

Unfortunately for free will, it doesn’t seem compatible with indeterminism either. To illustrate, take a famous thought experiment.

The Rewind Button

What would be required to empirically test whether or not the universe is determined or indetermined? Well, we’d have to perform multiple tests holding every single input identically the same, and see if we ever get a different output.

If we ever got a different output – and we knew all the inputs were identical – we could conclude that the universe is indetermined.

Just one problem: we can’t possibly perform this test, because we can’t control every single variable in the universe. In essence, we’d have to be able to perform an experiment, then “rewind the universe” to the exact state it was prior to the experiment, then replay the experiment over and over.

While we can’t actually do this, we can certainly think about it.

We’ve only two possible outcomes: either the exact same inputs yield the exact same outputs, or the exact same inputs yield different outputs.

Put more concretely, let’s revisit breakfast. Imagine all of the inputs leading to “the act of drinking water” were the same. If the output always yielded “drinking water”, then how can we say there was any choice in the matter? Given the same inputs, you always get the same output. Given your particular state of mind, you always make the same decision.

But what if the test yielded indetermined results? What if you had the exact same inputs, but, say, 90% of the time you chose water, and 10% of the time you chose orange juice. All of your beliefs, values, dispositions, capacities, etc., are the same, but one out of ten times, you drank orange juice.

How is this different than saying, “Without cause – by random chance – you drank the juice 10% of the time.”

If all of your evaluations are identical (all of your inputs are the same), but your outputs are different, that doesn’t seem like an act of will – that seems like an act of chance.

“Free will” and “random chance” are mutually exclusive, therefore, the argument concludes: neither indeterminism nor determinism leaves room for free will. Conceptually, it just isn’t possible.

It Could Be Otherwise

I think this argument makes a mistake. The dichotomy between determinism and indeterminism – as it’s been presented – doesn’t actually cover all the bases. There is another option.

The error is twofold. First, the indeterminist position overlooks a possibility. Second, the “rewind button experiment” is constructed incorrectly. As I said earlier, I won’t make a positive case for free will, but I will argue it’s conceptually coherent.

Simply put: indeterminism doesn’t necessarily imply randomness.

We have a third option between “causally determined” and “random”. It’s called “volitional”.

This morning, I could have chosen orange juice or water. Both were possible alternatives. But the non-volitional inputs were not sufficient to compel a necessary output. A volitional actor does not behave like billiard balls. External inputs are not always sufficient to compel an output, though they may affect it.

This doesn’t mean that the output was random, either; it was chosen.

If this sounds preposterous, let me be clear: if free will exists, it must be given a unique metaphysical existence. A radical, damn-near-supernatural kind of existence. We’re saying, explicitly and by definition, that “free will” is:

A mechanism in which the inputs do not necessarily determine the outputs. Yet, these outputs are not random; they are volitional.

In other words, we’re saying free will breaks all the rules. Everything we know in the universe operates according to the input-output principle, except for this one thing. The output of a freely-choosing conscious agent is not solely determined by the circumstantial inputs – rather, his “will” takes center stage.

Rewinding History

How does this conception of free will fit into the “rewind button” thought experiment? Here we find the second error. It is misleading to ask, “given the exact same inputs, would you get an identical output?”

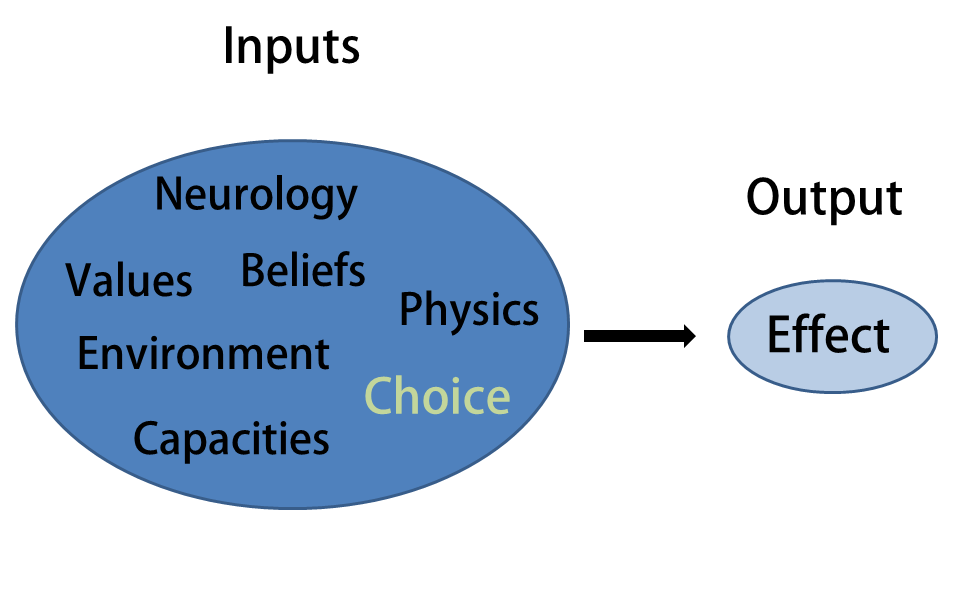

This lumps “the volitional choice” into one of the inputs. Here’s a diagram of the error:

The real question, as it pertains to free will, is rather, “given the exact same inputs except for your choice, could you have a different output? Or, does your volitional choice make the ultimate determination of the output?”

To put this question concretely, let’s go back to breakfast. It’s a mistaken question to ask, “Given the exact same inputs, including your choice to drink water, could the output ever be different?”

The pertinent question is, “Given the exact same inputs (your beliefs, your values, the environment, your capacities, etc), could you change one variable – your volitional choice to drink water – and cause a different output?”

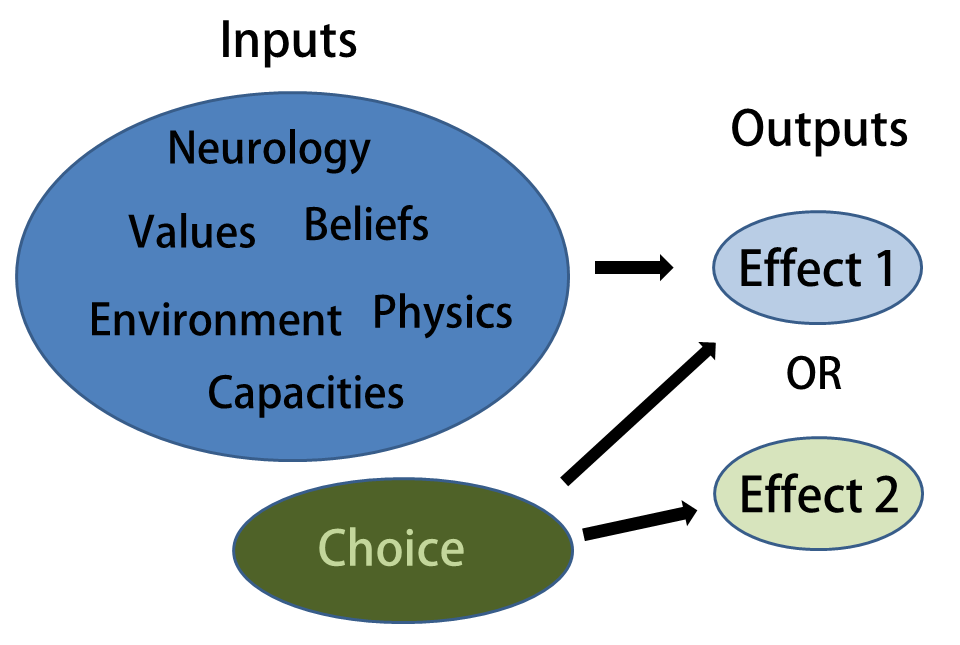

Here’s what the diagram should look like:

Where depending on what the “choice” is, you get a different effect.

So the natural question is, “But how could you change that one variable? What’s the cause of the change in volition?”

The answer is unsatisfactory, circular, but logically possible: that’s precisely what “volition” is – a consciously changeable input. Our volition doesn’t have to change due to randomness or pre-determined causes; it’s willfully chosen.

Implications and Presuppositions

Now, though I claim this is logically possible, it must be with a few constraints.

Assuming free will exists, we musn’t just ask, “What is the cause of the outputs of our volition (i.e. why do we make the decisions we make)?”, but rather, “What is the cause of the existence of our volition in the first place? How did such a thing come to be?”

Here, we run into a serious problem: it cannot be that we chose to have volition. This would be a vicious circle – we logically cannot have had the freedom to choose our volition in the first place.

So, if we do indeed have free will, we musn’t ultimately be responsible for the existence of it. That doesn’t mean, however, as is popularly concluded, “Because we couldn’t have chosen free will, we don’t ultimately have free will.” That conclusion is premature.

As far as I can tell, there are three possible explanations for the initial possession of free will: the naturalistic explanation; the theistic explanation; and the transcendental explanation. None are palatable.

The most absurd is the naturalistic explanation. Through a causally determined series of events, the most extraordinary phenomena happened: the chains of causality broke by themselves! Like a grand chemistry experiment resulting in the most radical of explosions. If the universe were like a pool table – and the matter which constitutes the universe are like pool balls – then through a grand “break” of the pool balls, somehow the universe wound up with self-directing pool balls, that move on their own conscious volition. This is, to me, the height of absurdity – though, it’s logically possible.

The next possibility is the theistic, or traditionally religious, explanation. We are “given” free will as a gift from a higher power. It’s a pre-packaged mechanism. That way, though we aren’t chronologically responsible for our possession of free will, we can still exercise it freely. It’s not an “ultimately free will” – as we aren’t responsible for having it – but it’s still a radically, meaningfully free will. This is also quite consistent with the religious philosophy regarding “objective morality”. We have a supernatural obligation to follow the moral rules given to us by the will-giver – like a child given keys to an extremely fast (and dangerous) car. We have the most harrowing responsibility – we can actually choose “good” from “bad”.

The final possibility is the transcendental – or perhaps “Eastern” – explanation. We have free will, but it wasn’t given to us, nor did we stumble into it. Rather, we always had it. Essential to Eastern religion is the idea of unity of the self with the transcendent – with the universe, with God, with everything. If you are ultimately God, then there’s nothing to give to anybody. You certainly didn’t give free will to yourself. You have it because you’ve always had it. It’s simply being realized in the particular version of yourself.

No Easy Option

It’s tempting to say, “Bah, these three possibilities are ridiculous! It’s much easier to accept that free will doesn’t exist.” But unfortunately, you can’t escape the absurdity, even if you deny the existence of free will. You have to reckon with the following, undeniable fact:

The perception of free will is a real phenomenon.

Not only do we seem to experience free will, but we experience it all the time, every day, as absolutely essential to our existence. Our entire identities are based on the presupposition of free will; we don’t think of ourselves as purely determined machines. So here’s the absurdity:

What is the evolutionary explanation for the existence of an illusory perception of free will?

Think about it. Consciousness takes an enormous amount of resources – blood, oxygen, a complex brain, etc. If free will is merely an illusion and is non-causal, then why in the world do we have such an extraordinary perception? The answer must be: no reason at all. We’re saying the illusion is entirely non-causal, ineffectual, and useless. It serves no purpose, by definition.

It is the grandest of tricks. The universe – a gigantic mechanical machine – happens to lay the groundwork for the emergence of conscious (mechanical) beings, who walk around talking to themselves having the illusory perception that they can choose to do things. In fact, this perception is so strong that their entire lives revolve around it. That somehow, they can control the chains of causality.

But they can’t, and it’s just a useless trick, that happens to cost a lot of physical resources and serves absolutely no function.

The notion is absurd.

Unfortunately, I don’t see any alternatives. Either the universe has a staggeringly, incomprehensibly absurd sense of humor, or our experiences are not illusory – and we’re essentially little angels.

In my own worldview, I don’t have a clear answer. I waffle between the options, depending on the day of the week. I am especially upset by the following idea: if I believed that free will didn’t exist, I would act differently. How preposterous.